Historians deserve credit for emphasizing the important but once overlooked fact that enslaved Africans in the Caribbean assiduously resisted slavery. Slave resistance took many forms, including daily acts of resistance, marooning, strikes and revolts. Some authors, however, point to the fact that many more men than women fled slavery. If this is true, it in no way detracts from the unique place that enslaved women deserve in the history of West Indian marronage.

The origins of the maroon communities

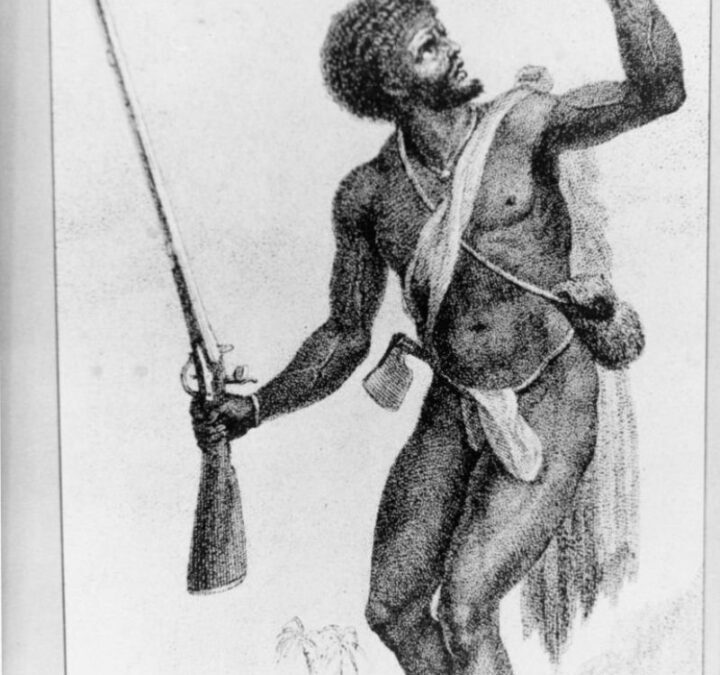

Marronnage was a direct form of resistance to slavery, involving unauthorized absences from servile tasks. It took place on two levels: small-scale and large-scale. Small-scale marronage was temporary and rarely involved violence or destruction. It was motivated by the need to be with loved ones, to experience short-term freedom or to test the prospects of permanent freedom, or in response to ill-treatment such as corporal punishment, hard labor or rape. Grand marronnage, on the other hand, aimed at permanent desertion from the plantation accompanied by violence, and was arguably the most successful attack on slavery, since it meant living a life of freedom in the midst of slavery. Escape from slavery, large or small, represented a deliberate disregard for the authority of the white master class to limit the slaves’ mobility and command their labor.

It was also a nuisance for colonial plantations, as maroons often resorted to raiding estates to satisfy their basic needs for food, tools, weapons and even women.

Many historians agree that the invisibility of women in this truly dynamic form of resistance can be explained by the demands of motherhood and child-rearing, the fear of reprisals and the unwillingness or inability to confront the treacherous terrain of refugee hideouts, which relegated women to the periphery of maroon activities.

Indeed, the risks faced by both male and female maroons were intimidating. Flogging, forced labor in workshops, hanging, transportation, separation from family, imprisonment, branding, gallows, rape and dismemberment were just some of the terrible consequences awaiting the enslaved fugitive who was caught alive. And yet, some enslaved women defied the odds by embarking on marronage.

In Barbados, for example, female slaves were particularly notorious for harboring enslaved fugitives. These brown collaborators provided enslaved fugitives with food, shelter, clothing and information. To curb this phenomenon, the Barbados Assembly enacted a law in November 1731 that punished 20, then 39 lashes and the branding of the letter R on the right cheek for first, second and third offenses respectively.

Women enslaved in Barbados in the late 18th century, according to Barry Higman’s findings, also made their mark in petty marooning, slightly outnumbering the men involved in this form of resistance at the time.

Maroon tactics to evade capture

Another demographic rarity is the eyewitness account of two captured maroons from the Windward group in Jamaica, who stated that in 1733 and 1734-35, the population of maroon women and children together far exceeded that of the men.

Enslaved women also joined men in maritime marronage. In St John, in the Danish West Indies, one of the best-documented episodes of maritime marronage took place on the night of May 24, 1840. Eleven enslaved people stole a boat and set sail for neighboring British Bermuda, where slavery had been completely abolished since 1838. Three of these maritime maroons were women: Kitty, Polly and Katurah.

The historiographical profile of enslaved women in the maroon movement is further strengthened by the impressive list that exists, which includes women such as Lise the midwife, Romaine, La Prophétesse, Marie-Jeanne, Henrietta, Rosette and Zabeth, all from St Domingue and Coobah from Jamaica. Coobah, according to the diary of her master, Thomas Thistlewood, was a recidivist. She ran away eight times in 1770 and five times in 1771.

Queen Nanny de Maroons: an emblematic leader

The quintessential Maroon woman who should answer all questions about the tenacity of the enslaved woman in pursuit of the fugitive life is Nanny, leader of the Windward Maroons in Jamaica. Nanny was skilled at guerrilla warfare, which she and her band of brigands used to eliminate the technologically superior British military raids that continually attempted to drive the maroons from their strongholds.

According to legend, Nanny also caught bullets with her hands or buttocks and « farted » them at her enemies. Tradition also mentions Nanny’s cauldron, a legend that reinforces her role as military defender of the chestnuts and highlights her skills as an herbalist. The legend of the pumpkin seeds underscores her role as agronomist, responsible for feeding and sustaining the community. Nanny, the brown woman of Jamaica, was as remarkable, if not more so, than her male counterparts such as Juan de Bolas, Cuffy, Cudjoe and Accompong.

The women who lived in the maroon camps were by and large essential to the survival of the community. They were mainly farmers, ensuring that the bands of fugitives had enough to eat. Their other tasks included reproducing the maroon population and reviving African cultural and religious practices through their role as priestesses and teachers of oral traditions.

Maroon women also helped the men defend the camps against white raids.

A dominant representation of maroon women, which has unfairly marked their profiling, is their depiction as passive captives caught up in plantation raids led by maroon men. This is a Eurocentric interpretation of the facts. It should be stressed, however, that the capture of these women was the ultimate act of resistance to slavery. Their new life in the maroon camps, even if tightly circumscribed by the men who had freed them, was far better than the one they led in slavery. For the multiple and profound ways in which the region’s Maroon women, though few in number compared to the men, used marooning to resist slavery, they deserve to be « historicized » as « sheroes » of the African diaspora.

The Maroons’ legacy in the struggle for justice and equality

The legacy of the Maroons is still felt today in the Americas, both in the cultural practices and traditions of their descendants and in the political struggles for justice and equality. The Maroons were pioneers in the struggle against slavery and colonialism, and their stories continue to inspire those fighting for a better world.

In conclusion, marronage may originally have been a punishment, but the Maroons turned it into a form of resistance and survival. The Maroons are a testament to the human spirit, the power of community and the resilience of the human body and spirit. Their legacy reminds us that even in the darkest of times, there is always hope for a better future.

See also our article: Maroons