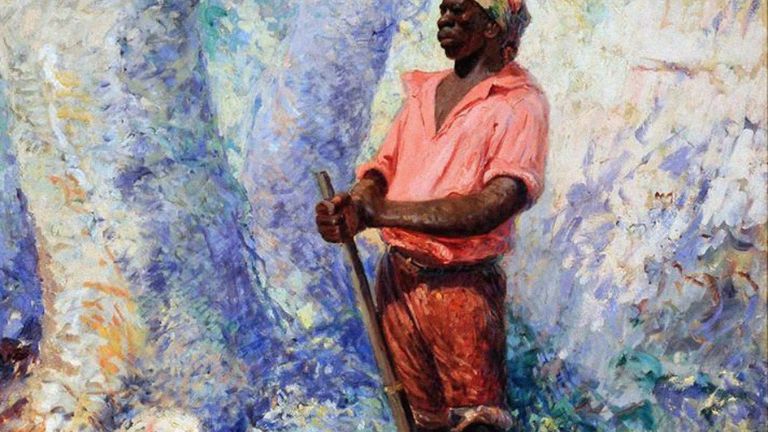

The name marron refers to an African or African-American population that freed itself from slavery and lived in hidden villages or towns outside the plantations. Slaves used various forms of resistance to combat their captivity, ranging from slowing down the pace of production and degrading tools to total revolt and escape. Some who freed themselves erected permanent or semi-permanent towns in hidden locations not far from the plantations, a process known as marronage (sometimes also spelled maronnage or maroonage).

The term« maroon » refers to Africans or African-Americans who freed themselves from slavery and lived in communities outside the plantations.

This phenomenon is known the world over wherever slavery was practiced.

Several long-established American communities were established in Florida, Jamaica, Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Suriname.

Palmarès in Brazil was a maroon community of people originally from Angola that lasted for almost a century, essentially an African state.

Those who freed themselves in North America were mostly young people and men, who had often been sold several times. Before the 1820s, a few headed west or to Florida when it was owned by the Spanish. After Florida was officially recognized as part of the U.S. territory in 1819, the majority headed north. The intermediate step for many of these would-be freedmen was marronage, where they hid relatively close to their plantations, but with no intention of returning.

The marronnage process

Plantations in the Americas were structured in such a way that the large house where the European owners lived was in the center of a large clearing. The cabins where the bonded laborers lived were located far from the plantation house, on the edge of the clearing and often in the immediate vicinity of a forest or swamp. Enslaved men supplemented their own diet by hunting and foraging in these woods, while exploring and learning the terrain.

The plantation workforce consisted mainly of enslaved men, and while there were women and children, the men were the ones most likely to leave. As a result, the new Maroon communities were little more than camps with unbalanced demographics, composed mainly of men and a small number of women, and very rarely of children.

Even after they had settled, the nascent Maroon communities had little prospect of forming families. The young communities had difficult relations with the slaves left behind on the plantations. Although the Maroons helped members of their community to free themselves, maintained contact with family members and traded with enslaved plantation workers, they sometimes looted these workers’ cabins for food and provisions. Occasionally, enslaved plantation workers (willingly or unwillingly) actively assisted their slaveholders in recapturing freedom seekers. Some of these all-male settlements were violent and dangerous. But some of these colonies ended up with a balanced population, and prospered and grew.

Maroon communities in the Americas

The word « marron » traditionally referred to the self-freed slaves of North America, and probably comes from the Spanish word« cimarron » or« cimarroon« , meaning « savage ». But marronage broke out wherever people were enslaved, and whenever whites were too busy to be vigilant. In Cuba, villages made up of freedom-seekers were referred to as palenques or mambises; in Brazil, they were called quilombo, magote or mocambo. Long-term marronage communities were established in Brazil (Palmares, Ambrosio), the Dominican Republic (Jose Leta), Florida (Pilaklikaha and Fort Mose), Jamaica (Bannytown, Accompong and Seaman’s Valley) and Suriname (Kumako). By the late 1500s, there were already brown villages in Panama and Brazil, and Kumako in Suriname was established at least as early as the 1680s.

In the territories that were to form the United States, Maroon communities were most widespread in South Carolina, but were also established in Virginia, North Carolina and Alabama. The largest known Maroon communities in what was to become the United States were formed in the Great Dismal Swamp on the Savannah River, on the border between Virginia and North Carolina.

In 1763, George Washington, the man who would become the first President of the United States, surveyed the Great Dismal Swamp, with the intention of draining it and making it suitable for cultivation. The Washington Ditch, a canal built after the survey and opening the swamp to traffic, was both an opportunity for Maroon communities to settle in the swamp, but also a danger, as white men looking for former slaves could find them and catch them living there.

Communities in the Great Dismal Swamp may have begun as early as 1765, but they had become numerous by 1786, after the end of the American Revolution, when slaveholders were able to pay attention to the problem.

Maroon communities varied greatly in size. Most were small, between five and 100 people, but some became very large: Nannytown, Accompong and Culpepper Island had hundreds of inhabitants. Estimates for the Palmares in Brazil vary between 5,000 and 20,000.

Most were short-lived; indeed, 70% of Brazil’s largest quilombos were destroyed within two years. However, the Palmares lasted a century, and the black Seminole towns – towns built by Maroons allied with Seminoles in Florida – lasted a few decades. Some of the Maroon communities in Jamaica and Suriname founded in the 18th century are still inhabited today by their descendants.

Most Maroon communities were formed in inaccessible or marginal areas, partly because these areas were unpopulated, and partly because they were difficult to access. The Black Seminoles of Florida found refuge in the swamps of central Florida; the Saramaka Maroons of Suriname settled on riverbanks in deeply forested areas. In Brazil, Cuba and Jamaica, people fled to the mountains and settled in densely vegetated hills.

Brown towns almost always included several security measures. Firstly, the towns were hidden, accessible only after following obscure paths that required long walks over difficult terrain. In addition, some communities built defensive ditches and forts, and maintained well-armed, highly trained and disciplined troops and sentries.

Many Maroon communities began as nomads, often moving for security reasons, but as their populations grew, they settled in fortified villages. These groups frequently raided settlements and plantations for goods and new recruits. But they also traded crops and forest products with pirates and European traders for weapons and tools; many even signed treaties with different parts of competing colonies.

Some Maroon communities were farmers in their own right: in Brazil, Palmares settlers grew cassava, tobacco, cotton, bananas, corn, pineapples and sweet potatoes; Cuban colonies depended on bees and game. Many communities blended the ethnopharmacological knowledge of their African homelands with indigenous and locally available plants.

In Panama, as early as the 16th century, palenqueros allied themselves with pirates such as the English privateer Francis Drake. A Maroon named Diego and his men led land and sea raids with Drake, and together they sacked the city of Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola in 1586. They exchanged vital information on when the Spanish would move the looted American gold and silver, and traded them for enslaved women and other items.

Maroons of South Carolina

By 1708, enslaved Africans made up the majority of South Carolina’s population: the largest concentrations of Africans at the time were on the coastal rice plantations, where up to 80% of the total population – white and black – were slaves. There was a steady influx of new African slaves throughout the 18ᵉ century, and by the 1780s, a third of the 100,000 bonded laborers in South Carolina had been born in Africa.

Total Maroon populations are unknown, but between 1732 and 1801, slaveholders advertised in South Carolina newspapers for more than 2,000 who had freed themselves. Most returned voluntarily, starving and freezing, to friends and family, or were hunted by groups of overseers and dogs.

Although the word « Maroon » isn’t used in the documents, South Carolina’s slavery laws define them quite clearly. « Short-term fugitives » were sent back to their slaveholders for punishment, but « long-term fugitives » from slavery – those who had been away for 12 months or more – could be legally killed by any white person.

In the 18th century, a small Maroon colony in South Carolina included four houses in a square measuring 17×14 feet. A larger one measured 700×120 yards and included 21 houses and cultivated land, housing up to 200 people. The inhabitants of this town grew rice and domestic potatoes, and raised cows, pigs, turkeys and ducks. Houses were located on the highest elevations; enclosures were built, fences maintained and wells dug.

An African state in Brazil

The most prosperous Maroon colony was that of Palmares in Brazil, established around 1605. It became larger than any North American community, comprising over 200 houses, a church, four forges, a six-foot-wide main street, a large meeting hall, cultivated fields and royal residences. It is believed that Palmares was made up of a core group of people originally from Angola, who essentially created an African state in the Brazilian hinterland. An African-style system of status, birthright, bondage and kingship was developed at Palmares, and adapted traditional African ceremonial rites were practiced. A series of elites included a king, a military commander and an elected council of quilombo chiefs.

Palmares was a constant thorn in the side of Portuguese and Dutch settlers in Brazil, who waged war on the community for most of the 17th century. Palmares was finally conquered and destroyed in 1694.

Maroon societies were an important form of African and African-American resistance to slavery. In certain regions and during certain periods, communities entered into treaties with other settlers and were recognized as legitimate, independent and autonomous bodies with rights to their lands.

Legally sanctioned or not, communities were omnipresent wherever people were enslaved. As American anthropologist and historian Richard Price has written, the persistence of Maroon communities for decades, even centuries, is a « heroic challenge to white authority and living proof of the existence of a slave consciousness that refused to be constrained » by the dominant white culture.

See also our article: Marronnage and the Maroons